Wrapping (also referred to as swaddling) is a useful strategy that parents can use to help their babies settle and sleep on their back, however there is limited evidence that infant wrapping has a protective effect against sudden unexpected death in infancy.

To Reduce the Risks of Sudden Unexpected Deaths in Infancy (SUDI), including SIDS and Fatal Sleep Accidents

1. Always place baby on their back to sleep, not on the tummy or side

2. Keep baby’s face and head uncovered

3. Keep baby smoke free, before birth and after

4. Safe sleeping environment night and day

5. Sleep baby in their own safe cot in the same room as an adult care-giver for the first six to twelve months

6. Breastfeed baby

Sudden Unexpected Death in Infancy (SUDI) refers to all cases of sudden and unexpected death in infancy and includes deaths from the Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) and fatal sleeping accidents. Safe sleeping recommendations target known risk factors associated with SUDI. Where studies specifically define the population as SIDS, this specific term will be used to describe the study findings.

- Wrapping, when used appropriately, is a useful strategy that parents can use to help their babies to settle and sleep on their back during the early months of life 1-5.

- There is limited evidence that wrapping infants on the back has a protective effect against sudden unexpected deaths in infancy 1,3,5,6.

- Although there is no evidence that wrapping or swaddling is protective, there is no evidence that it is harmful if principles of safe wrapping (see also below) are applied 3,6.

- Wrapping and placing babies on the back provides stability and helps to keep babies in the recommended back position 1,2.

- Being wrapped and placed on the tummy is associated with a greatly increased risk of SUDI and should always be avoided 1,6,7.

- Using principles of safe wrapping will reduce risks associated with infant wrapping and swaddling.

- When wrapping baby, allow for hip flexion and chest wall expansion.

- Ensure baby is not over dressed under the wrap, has the head uncovered and does not have an infection or fever.

- Babies must not be wrapped if sharing a sleep surface (including bed-sharing).

- Discontinue wrapping baby as soon as baby shows signs of attempting to roll.

Terms

Both the terms wrapping and swaddling have been used in literature to describe the practice of wrapping a baby in a cloth or blanket 8. Evidence from a Queensland study of maternal and child health professionals (n=161) suggested that the term ‘wrapping’ was clearly preferred over the term ‘swaddling’ (116, 72%), and that wrapping was frequently initiated by health professionals (126, 78%) as an infant settling strategy for parents to use if appropriate to family circumstances 4. Health professional responses indicated that language was important as the term wrapping was interpreted as firm wrapping of the infant in a piece of material for the purpose of settling and soothing an infant; while the term ‘swaddling’ was suggestive of loose or tight wrapping of the baby, or bundling of the baby in, or on, clothes and blankets for soothing or sleep 4.

For the purpose of this information statement, the term infant ‘wrapping’ will be used.

Background

Research has shown that one of the best ways to reduce the risk of SUDI, including SIDS and fatal sleeping accidents, is to sleep babies on their back. Managing unsettled infant behaviour and promoting sleep for babies, whilst ensuring that the safe sleeping recommendations are followed, is sometimes difficult for parents 4,9. Wrapping, sometimes referred to as swaddling, is a useful strategy that parents can use to help their babies to settle and sleep on their back, especially during the early months of life, and before their baby attempts to roll.

Wrapping or swaddling an infant has been described as an ancient practice of encircling an infant in a cloth or blanket to restrict movement 4,8,10. Techniques used to swaddle or wrap vary across cultures, and continues today as a common infant care strategy used by parents and carers all over the world 1,4,6,8,10-12.

Current Evidence

Studies have demonstrated that there are advantages and disadvantages of infant wrapping which primarily relate to the techniques or materials used in wrapping the baby, or other infant care strategies that are used in combination with wrapping.

Wrapping is a strategy that can be used to calm the infant and promote the use of the back position 1. Wrapping and placing babies on the back provides stability and helps to keep babies in the recommended back position 1,13-15 before a baby shows any signs of being able to roll 1.

Infant wrapping has been reported to reduce crying time 9,16,17 particularly for young infants whose parents reported excessive crying 9,17; shorten periods of distress 18,19; and improve baby sleep 2,10,13,14,20 by lessening the frequency of spontaneous arousals 2,13,17,20,21.

Wrapping a baby has not been shown to influence breastfeeding frequency and duration and the amount of ingested milk 21. Wrapping has also been shown to be effective in reducing a baby’s response to pain 2,22 while preterm babies who are wrapped and placed on their back show improved neuromuscular development 2.

Physiological data about the effects of infant wrapping on arousability to an external stimulus when infants are wrapped is conflicting 3,23. Studies by Franco and colleagues reported that babies who were wrapped were more likely to demonstrate reduced levels of motor activity in response to stimulation, fewer startles and lower heart-rate variability 20,24.

In contrast, a study 25 comparing infant physiology of infants who were routinely wrapped at home (n=15), with those naïve (unaccustomed) to swaddling (n=13), found differences between these two groups. These babies experienced both conditions, therefore acted as their own control. Infant wrapping did not alter sleep time, spontaneous arousability or heart rate variability for infants who were used to being wrapped 25; however for infants unaccustomed to swaddling at 3 months, cortical arousal was reduced and total sleep time was increased. This study 25 however, did not find that swaddling impaired sub-cortical arousals that are essential for adequate pulmonary function and appear to be the primary mechanism in terminating obstructive apnoea in infants 23,26. Richardson and colleagues 25 concluded that wrapping an infant naïve to wrapping may increase their risk of SUDI.

Although there may be minimal effects of routine swaddling on arousal 20,24,25 concerns have been raised relating to infants who are not used to being wrapped 25. Babies naïve to swaddling may experience reduced arousal the first time they are wrapped, which has been argued to possibly increase the risk of SUDI as babies are particularly responsive to changes in care and environment 3,25. This finding has led to a recommendation by some authors 25 that ideally, infants should be wrapped from birth, if parents choose to use this infant care strategy.

Wrapping techniques that use tight wrapping with the legs straight and together have been associated with an increased incidence of abnormal hip development 2,27. A review of research relating to wrapping has shown that tight wrapping with the legs held straight is associated with hip dysplasia and dislocation 2,27,28. When this practice is stopped, the frequency of dislocation is significantly reduced 29.

Swaddling babies is associated with increases in respiratory rate, likely due to decreased functional residual capacity resulting from increased extra thoracic pressure, created by a tight wrap around the baby’s chest 13,14,30 . Tight chest wrapping has been associated with an increased risk for pneumonia 31 . Some studies have indicated that overheating may occur if baby is heavily wrapped 32,33, or the baby is wrapped with their head covered, or if the baby has an infection 2,34 . It is therefore important to allow for hip flexion and chest wall expansion when wrapping 13,14 and to ensure that baby is not overdressed under the wrap, the head is uncovered, and the baby does not have an infection or fever 2,35.

Critiques of these physiological studies have suggested that there is insufficient evidence that infants who are swaddled on their back are at any increased risk of SUDI 3,23 . The advantages of swaddling back sleeping infants outweigh the risks 23 and swaddling is an important and appropriate tool in the care of the newborn 3.

Does infant wrapping reduce the risk of SUDI?

Tummy sleeping increases the risk of SUDI and must be avoided 1,5,36,37 . Wrapping a baby and placing them in the tummy position is even more dangerous as it prevents babies from moving to a position of safety 1,2,5,6,13 . If babies are wrapped, they should always be placed on their back 1,5 .

Several early studies provided evidence that infant wrapping may reduce SUDI risk when infants sleep on their back 38. Critiques of physiological studies have also suggested that there is insufficient evidence that infants who are swaddled on their back are at any increased risk of SUDI 3,23 .

A recent meta-analysis of four studies 6 which examined the association between swaddling and sudden infant death syndrome demonstrated that swaddling risk varied by the position placed for sleep; the risk was highest for sleeping on the tummy (OR=12.99 [95% CI: 4.13-40.77]); followed by side sleeping (OR=3.16 [95% CI: 2.08-4.81]) and then back sleeping (OR=1.93 [95% CI: 1.27-2.93]). Limited evidence suggested swaddling risk increased with infant age, and was associated with a twofold risk for infants over 6 months. This may be related to a greater likelihood of rolling to tummy position at an older age. A limitation of this analysis was that although infant age and sleep position were adjusted for, many other factors associated with sudden infant death were not adjusted for, including being swaddled while bed-sharing, or being swaddled and exposed to environmental tobacco smoke before and/or after birth. This meta-analysis concluded that current advice to avoid placing babies on their tummies or sides especially applies to babies who are swaddled. In addition, the increased risk of swaddling with age regardless of sleep position suggests that discussion needs to be encouraged relating to appropriate age limits for discontinuing swaddling.

Because of the likelihood of rolling onto the tummy, current advice for excessive crying in infants, suggests babies should not start wrapping after the fourth month, to un-swaddle as soon as the child signals they are trying to turn over, and always to stop swaddling before the sixth month, because after this age infants will be able to roll over 39.

When to stop wrapping

There is a greatly increased risk of death if a swaddled infant is placed in, or rolls onto their tummy 1,5-7,39,40.

Current evidence strongly suggests that as soon as baby shows signs of beginning to roll, wrapping should be ceased for sleep periods 1,5,6.

Special note about sick and low birth weight babies

Babies who are born preterm and wrapped during the period of hospitalisation have been shown to have improved neuromuscular development 2,41, less physiologic distress 16,18, better motor organisation and more self-regulatory ability 19. Swaddling has been shown to reduce behavioural distress after heel lancing in preterm infants older than 31 weeks but not in more immature babies 18. More recently a study conducted by Shu and colleagues 22 showed that both swaddling and heel warming reduced pain responses to the heelstick procedure in neonates born at 31-41 weeks gestation 22.

A study of preterm infants born less than 32 weeks gestation (n=100) investigated the developmental benefits of positioning in the neonatal intensive care unit 42. Using a randomised controlled trial design, babies were randomised to be positioned in an alternative positioning device (a stretchable cotton swaddle designed to provide containment while allowing the infant to move extremities into extension and recoil back into flexion) or to traditional positioning methods (wrapped in blanket and supported by nest) for their length of stay. Infants in the alternative positioning arm of the study demonstrated less asymmetry of reflex and motor responses than those positioned using traditional positioning methods 42.

In the early weeks of life however infant wrapping should not interfere with skin to skin contact of the low birth weight infant with a caregiver. Kangaroo mother care, or skin to skin, has been shown to reduce risk of mortality and morbidity and improve growth, breastfeeding and maternal-infant attachment outcomes for low birth weight babies 43.

Current evidence would suggest that sick or very prematurely born babies who were physiologically too fragile to be wrapped in the early weeks of life due to their extreme prematurity, medical condition or fragility are still able to be wrapped for settling and sleep as they grow.

It is advisable to introduce wrapping for settling and sleep as soon as the infant is medically well and sleeping on their back, prior to discharge from the neonatal care unit, to provide an opportunity for baby to be monitored and for staff to assist parents in practising safe wrapping strategies.

Special note about babies with clicky hips or congenital hip dysplasia

A review of research relating to wrapping has shown that tight wrapping with the legs held straight is associated with hip dysplasia and dislocation 2,27,28.

If a baby is diagnosed with congenital dysplasia of the hips, and parents wish to use infant wrapping as a settling and sleep strategy, specific advice from a health professional should be sought to ensure a safe technique is used that meets the individual needs of the baby.

Baby wrapping techniques

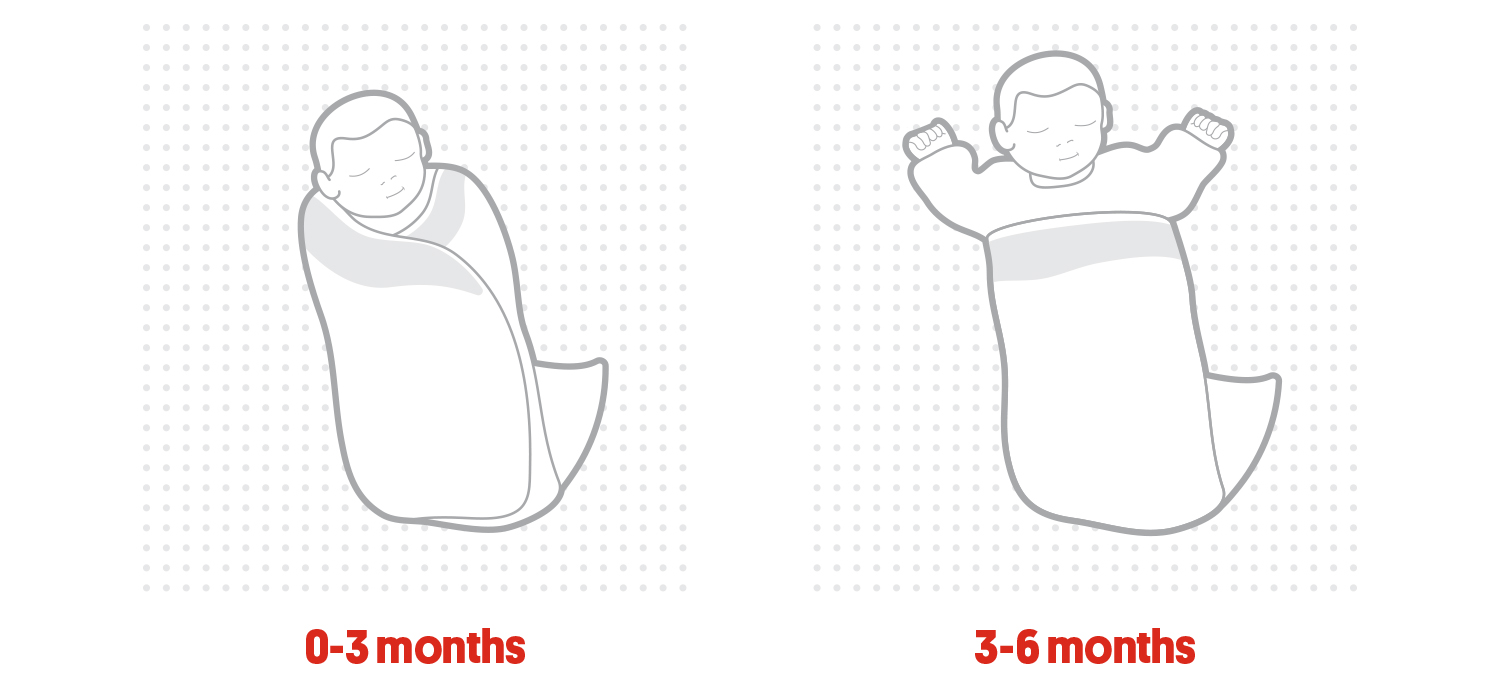

A variety of baby wrapping techniques appropriate to the baby’s developmental age can be used based on the principles of safe wrapping. For example, a younger baby (less than 2-3 months) may have their arms included in the wrap to reduce the effects of the Moro or ‘startle’ reflex; whilst an older baby (e.g. > 3 months) may have their lower body wrapped with their arms free, to allow the baby access to their hands and fingers which promotes self-soothing behaviour, while still reducing the risk of the baby turning to the tummy position. The Moro or ‘startle’ reflex should have disappeared by the time the baby is 4-5 months of age. There is no evidence with regard to SUDI risk related to the baby having arms inside or outside of the wrap. These decisions should be made on the individual basis, depending on the needs of the infant 1,5.

It is important to leave enough room in the wrap for the legs to move freely. The legs should be able to bend at the hips with the knees apart to help the hips develop normally.

Principles of Safe Wrapping

- Consider wrapping as a strategy to be used from birth or as soon as the baby is medically well and able to tolerate wrapping, in the case of premature or sick infants.

- Wrapping can be considered as a strategy to help older infants settle. It would be advisable that the first few times a baby is wrapped for an adult to check baby frequently as wrapping has been shown to reduce baby’s cortical arousal responses and increase total sleep time if they are not used to be wrapped, e.g. try several daytime naps in the first instance before wrapping for night-time or longer periods of day-time sleep.

- Ensure that baby is positioned on the back with the feet at the bottom of the cot.

- Ensure that baby is wrapped from below the neck to avoid covering the face.

- Sleep baby with face uncovered (no doonas, pillows, cot bumpers, lambs’ wool or soft toys in the sleeping environment).

- Use only lightweight wraps such as cotton or muslin (bunny rugs and blankets are not safe alternatives as they may cause overheating).

- The wrap should be firm, to prevent loose wrapping becoming loose bedding. However the wrap should not be too tight and must allow for hip and chest wall movement.

- Make sure that baby is not over dressed under the wrap. Use only a nappy and singlet in warmer weather and add a lightweight grow suit in cooler weather.

- Provide a safe sleeping environment (safe cot, safe mattress, safe bedding).

- Babies must not be wrapped if sharing a sleep surface (including bed-sharing) with an adult. Sharing a sleep surface with a baby can be hazardous in certain circumstances. See Red Nose information statement ‘Sharing a sleep surface with a baby’ for advice about sharing a sleep surface with a baby.

- Modify the wrap to meet the baby’s developmental changes, e.g. arms free once ‘startle’ reflex begins to disappear which is usually around 3 months; (Moro or ‘startle’ reflex should have disappeared completely by 4-5 months).

- As soon as a baby shows signs of beginning to roll, wrapping should be discontinued for sleep periods.

- The wrap may prevent an older baby who has turned onto their tummy during sleep from returning to the back sleeping position.

Examples of techniques that can be used to wrap a baby based on their developmental age. Reduce the effects of the Moro or startle reflex for a younger baby by including arms in wrap. Help an older baby stay on their back by wrapping their lower body, but leaving their hands and arms free to self soothe. Most babies eventually resist being wrapped.

The Red Nose ‘Safe Wrapping: Guidelines for safe wrapping of young babies’ pamphlet shows you how to wrap your baby safely [download here].

Infant Sleeping Bag

An alternative to wrapping is to use a safe infant sleeping bag; one with a fitted neck and armholes that is the right size for the baby’s weight. Clothing can be layered underneath the sleeping bag according to climate conditions.

There is some evidence that sleeping bags may assist in reducing the incidence of SIDS 1,5,44, possibly because they delay the baby rolling into the tummy position and eliminate the need for bedding. Further population based studies are necessary to improve understanding of how use of the sleeping bag may reduce the risk of sudden infant death. Current evidence suggests that use of a sleeping bag reduces the need for additional bedding which increases risk of head covering and potential suffocation, if it comes loose and covers the baby’s face. Sleeping bags should allow the legs and hips of an older baby who is able to roll to be able to move unrestricted.

Wrapping and swaddle products

A wide range of infant care products designed as infant swaddles, infant wraps, and wearable blanket, including products which attempt to combine the features of an infant wrap with an infant sleeping bag, have proliferated on the market and are available to parents 45.

It is important to be aware that there is very limited evidence to support the use of specific products as devices to promote infant settling, back sleeping position and no evidence to support these products as a strategy to reduce the risk of infant death. Parents are advised to follow the principles of safe wrapping if they choose to use infant wrapping as an infant care strategy. Parents are also advised to follow any safety advice that accompanies any infant wrapping or swaddle products they purchase, but to be aware that there is very little evidence available that supports the choice of one product over another.

In particular it is extremely important to ensure that the product fits the baby and is appropriate for their developmental stage. For example:

The material of the wrap or swaddle should not cover the face or head, particular if baby sleeps with arms in different positions. If the item is too big for the baby, some zipped swaddle suits that enclose baby’s hands, have been shown to allow material to cover baby’s face and nose when baby raises their hands above their head during sleep. All sleeping attire designed to cover the baby’s shoulders should have separate neck and arm holes or should ensure that they do not allow the face covering if the baby was to move their arms in different positions.

Any product that is used as clothing on the baby or in the baby’s sleep environment should not restrict the movement of a baby who is able to roll. Wrapping should be discontinued as soon as the baby shows the first signs of being able to roll. Positioning aids that restrict movement of the baby are not recommended and have been associated with infant deaths.

Key evidence summary points

- Being wrapped and placed on the tummy is associated with a greatly increased risk of SUDI and should be avoided 1,5-7.

- The advantages of swaddling back sleeping infants outweigh the risks 3,23 and swaddling is acknowledged as an important and appropriate tool in the care of the newborn 3.

- There are benefits associated with wrapping premature babies during their hospitalisation. Premature and sick babies who were not wrapped in the early weeks of life due to their medical needs are able to commence wrapping as soon as the baby is medically well and sleeping on their back; this is recommended prior to discharge.

- Infant wrapping must be correctly applied to avoid the possible hazards. Wrapping the baby does not reduce the need to follow safe sleep recommendations 1,5.

- Wrapping should be discontinued as soon as the baby shows signs of being able to roll 1,5.

In Australia, between 1990 and 2015 approximately 5,000 babies died suddenly and unexpectedly. Baby deaths attributed to SUDI have fallen by 85% and it is estimated that 9,967 infant lives have been saved as a result of the infant safe sleeping campaigns.

The Safe Sleeping program is based on strong scientific evidence, has been developed in consultation with major health authorities, SUDI researchers and paediatric experts in Australia and overseas, and meets the National Health & Medical Research Council rules for strong evidence.

For further information visit the Red Nose website at rednose.org.au or phone Red Nose on 1300 998 698.

Suggested citation:

Red Nose. National Scientific Advisory Group (2017). Information Statement: Wrapping infants. Melbourne, Red Nose. This information statement was first posted in October, 2005. Most recent revision April 2017.

View the references for this article here.

Last modified: 16/12/22